Week 21 Purnululu

In our twenties, Brodie and I travelled together for several months a couple of times, to Turkey, Europe and the UK. This time with her and John seemed so distant when we were in the south, in Margaret River, at Ningaloo and even travelling up the Gibb.

As we head south from Kununurra to Purnululu, I feel that the darkness of winter, the gloom and rain is looming. While the Purnululu sky is big, clear and cloudless, it marks the halfway point of our time together. As another low pressure system forms off the east coast, dumping record rainfalls, including 346 mm at Currarrong (John’s abreast of the news), we’re enjoying warm days and endless blue skies. It’s been a pleasure waking up with the sun, which rises a little later here on the west coast than in the east, tent windows open to the sky.

On our way we stop at the Warmun roadhouse, also known as Turkey Creek. This is now a Gija community, originally established in the early 1900s as a ration depot by the Department of Native Welfare because of the conflict between pastoralists and the original inhabitants. Some local people in 1977 petitioned the government to make it a permanent settlement for Gija people, following the equal wage legislation of 1968 which saw many Gija people losing jobs and subsequently access to country. Twice dispossessed.

The Spring Creek Road into Purnululu is notoriously rough – Parks suggests it takes two hours to travel the 53 kilometres. We don’t linger at the art centre but Jeremy does help Cecil, one of the local elders, chainsaw a piece of hardwood he intends on carving. Of all the Aboriginal art we have seen over the past few months, the Gija paintings of ochre reflecting the Purnululu range and often pastoral experiences of the painters, is among my favourite. We first saw it at the Artlandish Aboriginal Art Gallery in Kununurra.

We’re disappointed to miss the Warmun gallery but must press on.

Our first camp spot is at Kurrajong in the northern end of the park. We spend our three days here wandering through chasms, between crevices and below the folds in fiercely orange rocks towering above us, through brightly coloured stands of red, flame orange and yellow grevillea, wattles, Livistona palms and the shimmery silver box eucalypts.

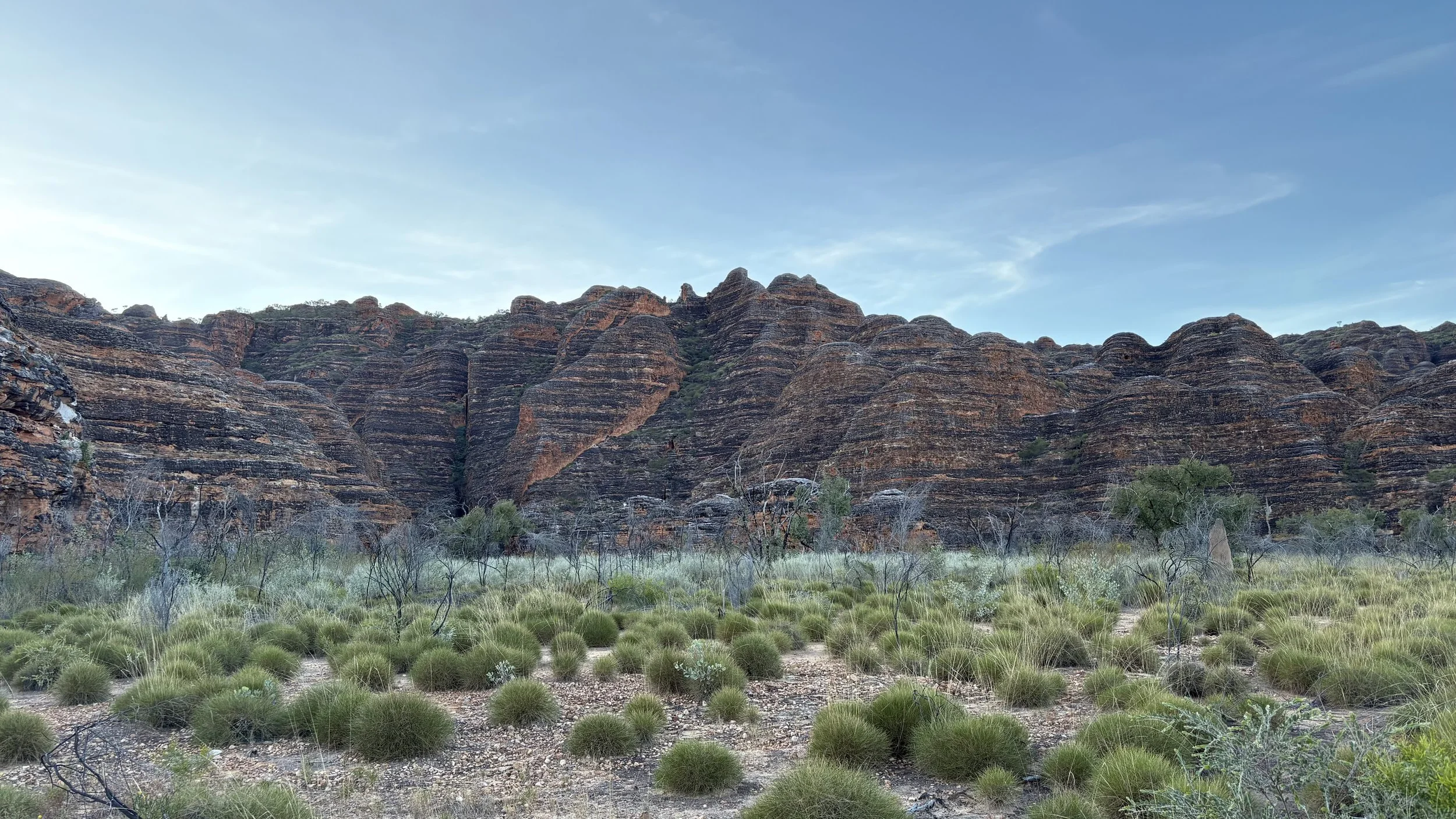

A UNESCO world heritage area, the iconic sandstone karst formations stand alone as the most diverse and spectacular of their kind in the world. The striking banded black and orange beehives have formed due to the unique interactions between geology, biology, climate and erosion. I won’t attempt to interpret the information I have read suffice to say, this is a special place. It’s surrounded by savannah grasslands with spinifex and mulga dominating the sand plains.

We walk up to Echidna Chasm twice, the second time to catch the fiery band of golden sunshine that illuminates the orange fissures high above. It is difficult to capture the scale of this place in words or with a photograph without someone in the frame to help with perspective. We head to Bloodwoods Lookout at sundown for a quiet beverage and to soak up the changing colours and light at the close of the day.

The Osmand Range to the west is twice as old as the Purnululu Range. Looking down from the Osmand Lookout, between the ranges on the valley floor, the eucalypts look to be recovering from fire, with blackened trunk and branch covered in soft, curling green regrowth. Although we don’t see any, there are art sites in this valley, a place used heavily by Aboriginal people before colonisation and pastoral exploits disrupted the native fauna and flora they relied on for food and survival. Surprisingly, given the arid climate of the park, the Osmand Range has permanent waterholes that sustain riverine ecosystems and water animals.

Tall, thin termite mounds, sentinels, stand above us on the escarpment as we enter gorges in both northern and southern ends of the park. They keep watch over the landscape from on high, light-coloured pillars. We also see the double barred finch here.

Walardi campground, located in the southern reaches of the park, gives us excellent access to the emblematic beehive formations. We arrive late morning in time to set up camp and drive the 15 kilometres to immerse ourselves in the afternoon light at the domes and Cathedral Gorge, a special place with abundant space and acoustics that would rival St Peter’s Basilica. What to sing? A hymn? We toss a few ideas around before singing Feeling Groovy, followed by a verse of Amazing Grace. We sense the sacred here in the rocks and feel dwarfed. Our significance isn’t much.

The domes are spectacular, rounded massif with bright green spinifex sitting in spiky hummocks around them, all the more bright because of the recent rains that kept the roads into this national park closed the longest.

We hike to Whip Snake Gorge, a 10 km return walk through the domes, along a dry riverbed with interesting rock formations underfoot – white, with its own unique ridged landscape. At the end of the gorge we linger, admiring colour, shape and scale.

We also spend time at camp relaxing and I send a few job applications – casual or contract work is what I am aiming for, happy to take a break from the intensity of a full-time full-on position.

Jeremy is keen to catch the early morning light so he and I wake up early and head to Picaninny Creek Lookout on our last full day for sunrise and we return to Cathedral Gorge. The domes at 5.30 am are awash in gentle lavender light. At Picaninny Creek Lookout, the scene is unreal, like a backdrop. The pink sky and high wispy clouds work in harmony with the domes, spinifex and mulgas. A symphony of white, green, silver, grey, sage and the orange-black bands of the rock. This place is otherworldly, from another universe. It’s Tolkein or Spielberg.

We enjoy a cup of tea at the lookout in the cold stillness of the morning before heading up to Cathedral Gorge where we bump into a school group from the Southern Highlands, NSW. I have actually sent an expression of interest to this school and we chat with the staff, one of whom has brought bagpipes to play here.

He serenades us out of the gorge, a beautiful way to end this special visit.

Sundowners later that afternoon are on a nearby rocky outcrop (in keeping with the spiky spinifex), at which point we think John acquired a tick, the first of the journey — amazing given the fact that we have been outdoors for the past five months. And at sunset the escarpment is gold veins glowing in layers beneath the spinifex and ghost gums atop the ridge.

We farewell Brodie and John at the highway following our six nights in this incredible landscape. Its been wonderful to travel with people who know us, who love and tolerate our foibles. The safety of friendship is a sweet space. Laughter at and with you but that’s AOK because we’re known and loved here with these people. Nothing better.

Halls Creek will be our last town before we hit the Tanemi Track to start the journey home. We decide that after our week of camping we’ll splurge for a room at the Kimberley Hotel. The decor is something special, from Carol and Mike Brady’s house. When we book in they tell us that there is secure parking, including an electric fence.

I tutor in the afternoon, we do a couple of loads of washing and enjoy the luxury of a bathroom with hot running water. Dinner at the bar is also exciting, particularly with karaoke, and we chat with a couple of groups of local mob over dinner and afterwards with a drink.

At Halls Creek, the bottle shop opens at 11 am and sells only light beer. There is one grocery shop, where a 1.2 kilogram box of weet-bix costs $10.15. Oranges sell for $9.99/kg, Imperial mandarins cost $12.99/kg, pink lady apples cost $12.99/kg, Josephine pears cost $11.99/kg and Fantastic Original Rice Crackers cost $3.40. The Shell servo is busy with road trains, caravans, camper trailers and 4WDs, the busiest place in town.

Shirley at the Visitor’s Centre is lovely and shares a lot of local knowledge with us. A google search will reveal Halls Creek as a place to access Purnululu or the Canning Stock Route, Wolfe Creek Meteorite and the Tanemi Track. It’s also been home to many many people for many thousands of years before Charles Hall struck gold here in 1885.

We leave the bitumen for the iconic and somewhat intimidating Tanemi Track, around 1030 km of mostly unsealed remote driving.